💡 Support Note: This issue includes a sponsored ad that helps us keep the newsletter free. A simple click makes a real difference — thank you!

Here’s What a 1-Day Gutter Guards Upgrade Should Cost You In 2025

Forget about climbing ladders or clearing wet leaves out of your gutters. Keep your home safe and boost its value with a simple, long-lasting solution. More than 410,000 homeowners already made the switch — and love the results.

Find out how it works and see local, no-middleman pricing today.

The photos in this newsletter help bring the story to life, but most are not from our family archive. We found them online to illustrate the atmosphere of the time, since we don’t have any pictures from our grandfather’s apprenticeship years. We’re grateful to the creators who shared them. Only two photos, at the end, are truly ours.

In the early 1960s, most people in Switzerland still bought their meat from the local butcher. There were no supermarket chains in every neighborhood, and meat didn’t come sealed in plastic. It was prepared fresh by people who knew the animals, the cuts, and the customers.

The apprenticeship system was already in place at the time, offering young people a way to enter a profession by learning directly from skilled workers.

This is the story of one of those apprenticeships.

It’s also the story of our grandfather.

Where It All Began

“I grew up in the countryside, in a family of farmers. At home, we butchered one pig each winter. Sometimes, when a calf didn’t survive, I’d sell its hide. I was fascinated by the craft. Even before I had the chance to set foot in a butcher’s shop, I knew I wanted to become a butcher.”

Butchering day on the farm — a traditional moment in rural life, often with help from a local “tchacaillon,” someone who assisted with home slaughtering.

“I’ll remember it all my life — when I told my mother I wanted to become a butcher, she said: ‘Oh yes, if you become a butcher, you’ll never go hungry.’ She didn’t just mean having steady work. She meant I’d always have food, even if times got tough. And she was right.”

The Rhythm of the Week

At the age of 17, in 1962, our grandfather began his apprenticeship in a small butcher shop called Balimann, located in Morges, a lakeside town near Lausanne. For the next three years, he learned every part of the trade.

Grand-Rue in Morges during the 1960s — today, it’s a pedestrian street.

“Mondays started before dawn. We were at the abattoir (the slaughterhouse) by 5:30 in the morning to process four pigs. By 7:30, we were back in the shop, cutting and deboning. In the afternoon, we made everything fresh — sausages, roasts, cured meats. Other cuts were hung to be prepared later in the week.”

A typical butcher shop display in Vaud — with pâtés, saucissons, salami, and other regional specialties.

Tuesdays were for cattle.

In the afternoons, he attended class for theory — part of the apprenticeship structure that combined working in the shop with classroom learning.

“On Wednesdays, we picked up the carcasses, stored them in the cold room, then spent the day cutting briskets, fronts, making ground meat and preparing roasts. It was hard, physical work.”

“Earlier in the week, customers mostly bought pork: sausages, chops, or sliced cuts. We didn’t start deboning the hindquarters — the part used for steaks — until Thursday. That’s when beef steaks became available in the shop. People knew the rhythm and planned their meals around it.”

Cutting pork in the workshop

The Hardest Part of the Job

Some tasks didn’t just require skill, they pushed the body to its limits and demanded full attention.

“The work was heavy. I remember one day in particular. I was 18. We had just returned from the abattoir with a bull. I had to carry its thigh, which weighed 115 kilograms (250 pounds). I lifted it from the truck, walked it through the street, across the shop, and into the fridge. Most of the time, the thighs were closer to 80 kilos (176 pounds), but this one... if you didn’t hold it the right way, you could fall with it.”

His Favorite Part?

“Roasts, skewers, brochettes, anything that would make customers happy. In winter, we even hung entire quarters in the front window. It looked impressive, and customers appreciated it.”

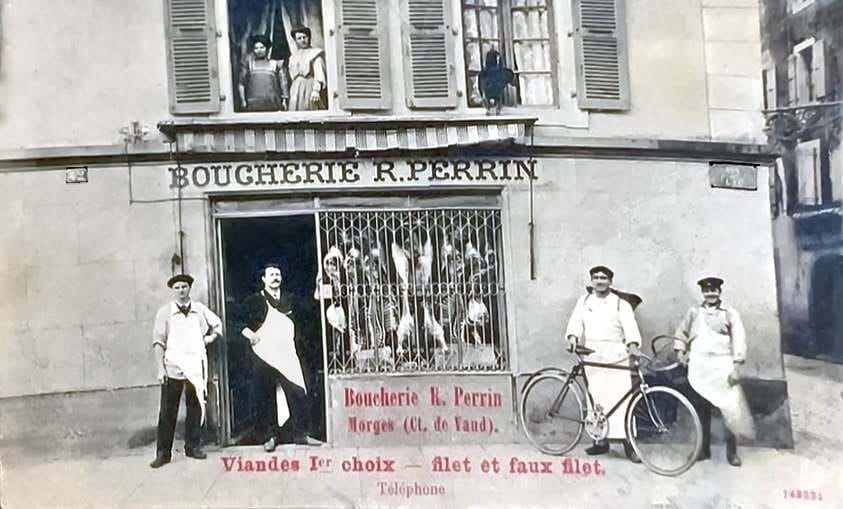

Perrin Butcher Shop, Morges, around the year 1900 — with the butchers proudly standing in front of their store.

What Has Changed

Some tools have evolved, but the fundamentals have stayed the same, at least in small shops.

“Now there are electric saws, meat grinders, and vacuum machines that help with storage. But deboning and cutting are still done by hand — a lot of tools haven’t changed.”

Making saucissons with a classic sausage machine — a tool still used in butcher shops… and in some kitchens too 🙂 My dad makes great sausages at home!

“There used to be many small butcheries. When I had mine, in the eighties, there were seven others. Now there are none. Big stores took over, and it’s much harder to find apprenticeship spots. In the countryside, there are almost no local shops left.”

“If you learn at a chain like Migros — Switzerland’s largest supermarket — they’ll train you their way: the industrial way, not the artisanal one. Their meat goes straight to the shelf. In small butcher shops like ours, we age the meat properly.”

“Most butchers today don’t slaughter animals themselves. They pick up the meat at the abattoir, already prepared or even pre-deboned. And most of the small, local abattoirs have closed.”

Easter cattle parade, 1925 — held three weeks before Easter to showcase the quality of the livestock. This tradition no longer takes place.

From Apprentice to Master

After his apprenticeship, our grandfather didn’t stop learning. He worked as a butcher in Australia — where he met our future grandmother — before returning to Switzerland. In time, he opened his own shop in Prilly, a town next to Lausanne. His butchery was a great success. He remained independent throughout his career, running the business all the way to retirement, and even beyond.

Our grandfather in his butcher shop — a place we’ve heard so much about, but never got to see.

Bernard Roch, our grandfather

You don’t have to be a butcher to understand what it’s about.

It’s about learning through doing. About working with your hands. About taking pride in what you create.

Butchery is one of many trades that are becoming rare — along with the apprenticeships that once passed them on.

And yet, they’re still important.

They teach more than a skill.

They teach confidence, patience, and care.

For us, writing this was also a way to get to know our grandfather better, to understand where he came from and the path he took.

We share his story because it’s worth remembering — a rare glimpse into the life of a young butcher’s apprentice in the 1960s, and everything it can still teach us today.

🎥 Want to see what a butcher’s apprenticeship looked like in the 1960s?

This short video, filmed in Switzerland in 1965, shows the tools, gestures, and atmosphere of the time. It’s in French — but worth watching even if you don’t understand everything.

🤝 Before You Go

🍞 Do you know someone, maybe in your family, with a skill that’s worth sharing or learning from?

💌 New here? You can still catch up — read our previous newsletters here.

🔁 And if you know someone who might need this newsletter today, feel free to forward it their way.

Solène and Zélia, for SoliaVenture

P.S. Since we live in the U.S., we miss this local specialty — pâtés vaudois. So we started making them at home…

If you're curious, here’s a link with more info.

Every bite feels like a little trip back to Switzerland.